Normally, I’m a software engineer. In particular, I specialize in architecting netcode for games. A few weeks ago, I departed a job doing just that at Super Bit Machine – the game I worked on for two years was successfully launched and I’m quite proud of the work I did on it.

That said, having most of December off gave me some time to work on personal projects and I ended up returning to an old hobby: messing around with electronic crap that I barely understood and probably have no business messing with.

In particular I’ve been tinkering with a technology I find absolutely fascinating: FPGAs.

FPGAs (Field Programmable Gate Arrays) are so interesting to me because not only is it a single simple chip that can be reprogrammed into almost any digital logic circuit you could possibly dream up, it also gives you a way to design your digital logic with very high-level concepts: using a language like Verilog, you can express your logic with high level syntax and let Verilog do the work of putting all of those low-level logic gates together for you (adders, comparators, multiplexers, etc).

However, FPGAs are also a little odd for me to mentally grasp. Remember, I’m a software engineer by trade. In computers, everything operates mostly sequentially. The hardest problems for us to solve are when they don’t – generally, multi-threaded code that allows multiple pieces of code to run at the same time and possibly try and interact with each other in unpredictable order can be some of the toughest designs to tackle.

By contrast, absolutely nothing in an FPGA runs sequentially unless you design it to. And yet I can’t resist the appeal of trying to work with them anyway. And that brings me to this project: Athena.

Athena is a little project of mine to implement a game console on an FPGA. Crazy (at least for me)? Possibly. But I frequently learn by tossing myself into the deep end of the pool so to speak, so honestly I’m not too worried.

Now, onto the design of the Athena.

Athena will be designed as a very retro console, aiming for something that would feel at home in the late 80s to early 90s. Think the 16-bit era of gaming. I want to make use of chips that would actually have been available for a console of the time, and this brings me to one of the reasons FPGA is a fantastic choice: I can grab old IC implementations mostly off-the-shelf and toss them into my FPGA design without having to scour Ebay for old chips that have been out of production for years. I can also custom design my own bespoke modules for when I need something that I just can’t find off-the-shelf.

That said, here’s what I’ve decided on for Athena:

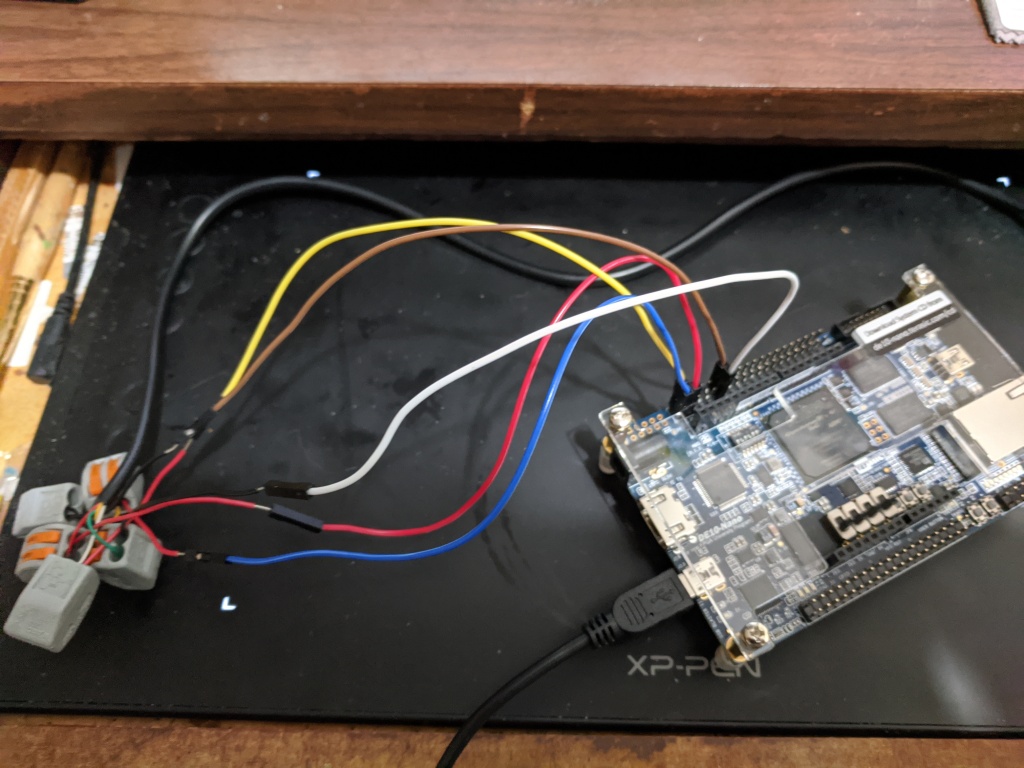

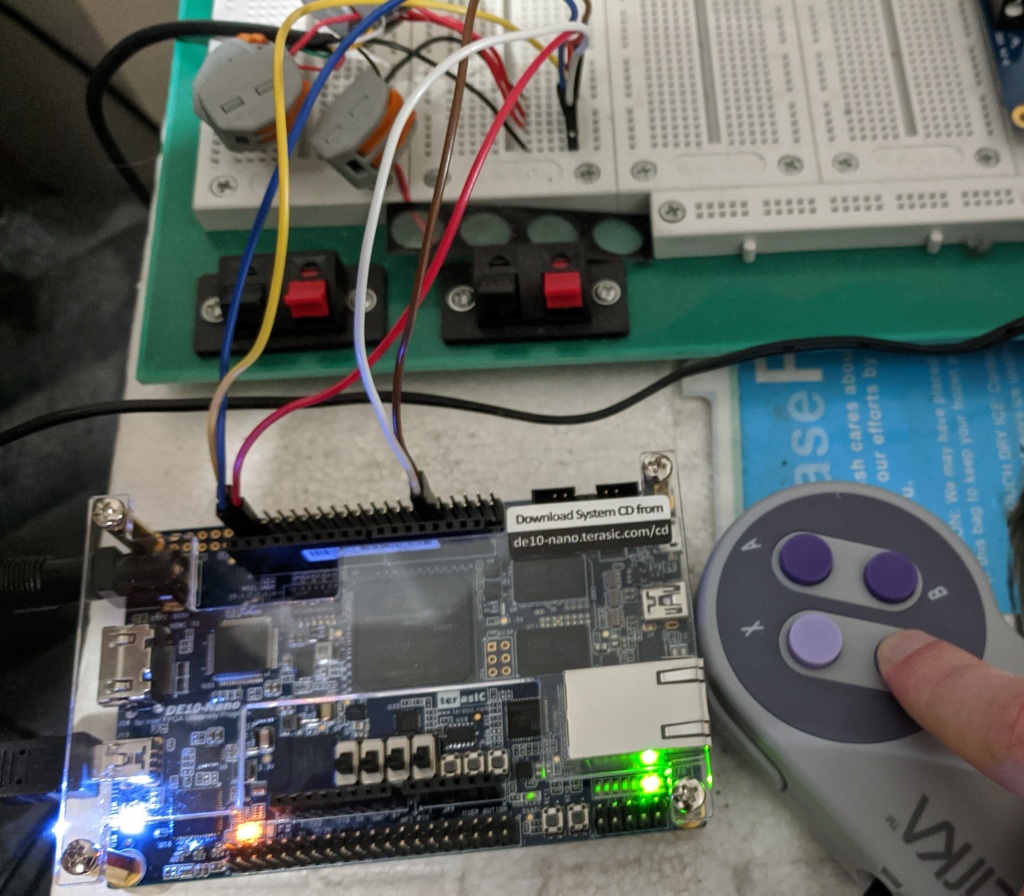

- I will be using the Terasic DE10-Nano as the development board for this project. To be honest, I was more than a bit inspired by MiSTer’s use of this board for their purposes. I figured if the board was good enough for a MegaDrive core, it should be good enough for me!

- The heart of the console will be a Motorola 68K CPU, clocked at 12.5 MHz (exactly 1/4 the board’s 50MHz clock speed. I was, and still am, tempted to clock it at 25MHz instead but that feels a little less authentic to me).

- 64KB of SRAM will be available to the CPU for code storage and general RAM.

- A bespoke video generator module will be responsible for driving 320x240p@60Hz video output, supporting two scrolling tilemap layers, up to 128 hardware sprites (up to 20 per scanline), and 256 colors per scanline with 4 bits per RGB channel. As the DE10-Nano has a video transmitter built-in, this will be done over the HDMI out. The video generator has 32KB of SRAM dedicated to storing color palettes, image data, tilemap data, and miscellaneous registers.

- A YM2151 chip and a bespoke 4-channel PCM chip will together be responsible for outputting 44.1KHz stereo 16-bit audio over the HDMI out. The 4-channel PCM chip will have 32KB of SRAM dedicated to storing 8-bit unsigned PCM samples. Both the YM2151 and the PCM chip will be memory-mapped into the M68K bus. The audio sample RAM will not, but more on that later.

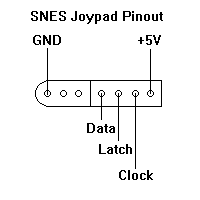

- The Athena will support two controller ports pin-compatible with the original SNES game controller, memory-mapped into the M68K peripheral bus with a serial-to-parallel interface on top to simplify interacting with them.

- A bespoke DMA controller will simplify interacting with memory that isn’t directly attached to the M68K bus – namely, the video RAM, and the audio sample RAM. Code running on the M68K will ideally be able to just signal a memory copy from main RAM to either VRAM or audio sample RAM, and the DMA controller will handle temporarily disabling any modules it needs to for the duration of the copy to prevent bus contention issues.

- The Athena will support the DE10-Nano’s onboard SD card reader, memory-mapped directly into the M68K peripheral bus with a serial-to-parallel interface on top to simplify interacting with it. An onboard bootloader ROM attached to the M68K bus will be responsible for loading a default boot program off of the SD card into the main RAM, making the SD card slot act essentially as the Athena’s game cartridge port (games can also use their own logic to drive the SD card slot, which could potentially be used for things like loading assets and storing game saves)

So, for a little while, I’m going to be chronicling my adventures in trying to design this daunting behemoth of a design. Will it end in absolute failure? Will it end in a cool working retro console? Who knows!

I guess we’ll see!

EDIT (12/24/2019 5:21 PM)

– It occurs to me that the SD card reader built into the Nano board CAN be controlled from the FPGA core, buuut it’s supposed to contain files that are important for both the HPS as well as the files to initialize the FPGA core on boot, so I’m a little more hesitant to use it as a makeshift cartridge slot now. Actually, I already have a separate SD card reader breakout board on hand, so I think I’ll just use that instead and wire it up to some GPIO pins.